If you ever had a feeling dragonflies were not as innocent as they appeared to be, you might have had a good reason.

In December 2003, the CIA held an exhibition at its museum near Washington where the agency displayed dozens of “top-secret” spyware and intelligence-gathering equipment. [1] Thousands of people realized that day that not even tiger poop was safe from imitation by the agency. Vietnamese soldiers probably had no idea what those brown lumps lying in the bushes were. Then there was the robotic catfish you would never guess was unreal, often placed in waters near nuclear plants to collect samples and monitor contamination. Well, that day, one particular device stole the entire show: the Insectothopter, otherwise known as the bug-carrying bug.

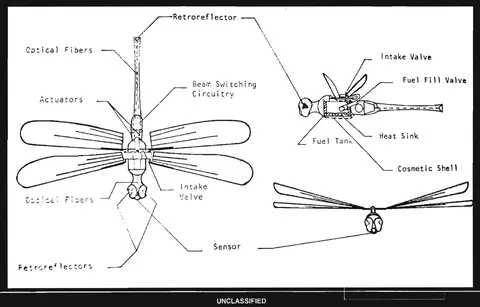

Although the CIA’s Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Program was commissioned in 2004 following the 9/11 attacks, this unique bug had taken its first flight in the 1970s. Almost 50 years later, this year, the agency finally released detailed workings of the bug. At first sight, it looks like any other dragonfly floating in the air and going about its business, but it’s one dragonfly with a mission essential to national security. It was developed by the Agency’s research and development office to gather intelligence and evade detection.

The engineers had wanted to deploy a bumblebee design, but the idea was scrapped after the prototype was tested. The bumblebee was extremely erratic in flight and more of a threat than an asset. Following the suggestion by an amateur entomologist, dragonflies were thought to be more realistic and practical. Naturally, these insects could hover, glide, and even fly backward. They are also found in every continent except Antarctica, so the dragonfly UAV could be deployed without raising suspicions.

How it works

This particular spyware was created to get into “enemy areas” that would have otherwise been difficult to access and monitor.

With a range of 200 meters and a flight time of 60 seconds, the remote-controlled Insectothopter, crafted by a watchmaker, had initially turned out to be a successful prototype. [2] It was painted in the natural colors and shaped in the exact contours of the most regular dragonfly you could imagine. It was powered by an ultra-small gas engine to propel its wings and was only fueled by a very little amount of gas. The tiny fluidic oscillator would propel the wings at the desired rate, providing a measure of lift and thrust, and extra thrust was derived from the rear gas vent of the bug.

According to the agency in a 2013 statement release [3]: “A laser beam provided guidance and acted as the data link for the audio sensor payload. This is the first flight of the insect-sized unmanned aerial vehicle called Insectothopter. Flight tests were impressive. Performance measures indicated a range of 200 meters and a flight time of 60 seconds with a 1-gram launch weight.”

The bug was deployed after a successful development, and while flight tests were relatively impressive, it was almost impossible to control in windy conditions. According to the agency, “…but because control in even a slight crosswind proved too difficult to overcome, Insectothopter never became operational.”

How did we get to know about this?

Although the CIA had displayed the dragonfly at its 2003 exhibition, a lot remained unknown about the device and its functions. However, in 2013, under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), John Greenwald Jr., author and anti-secrecy activist put in a request for the details of the bug to be released. Greenwald is the founder of The Black Vault, a website dedicated to “exposing the government’s secrets, one page at a time.”

The agency posted a few details of the bug in its website that year, but it wasn’t until January 2020 that the full documents were finally released to Greenwald.

Speaking to Popular Mechanics, he said: “I’ve learned over the years, the U.S. military and government often will acknowledge something or confirm something exists, and many times that largely satisfies the public’s curiosity,” Greenwald told Popular Mechanics. “However…we often don’t get the full story. So I go after documents never-before-released to tell either more of the story or the real story.” [4]

Well, even though the only Insectothopter ever created is reportedly locked day at the CIA’s museum, I’ll probably never look at dragonflies the same again.

The CIA has had other animal agents in the past, a lot of which didn’t last long or turned out to be major flops. In the ’70s, there was Project Tacana that velcroed cameras onto pigeons and sent them to get pictures of the Russian naval base in St. Petersburg. Project OXYGAS debuted in 1964 where dolphins were taught to attach tracking devices or explosive charges to submarines. It was one of the most successful and continued until 1969. One of the most controversial projects was Acoustic Kitty, where the agency surgically implanted a transmitter into the skull of a live cat, put a microphone in its ear, and an antenna on its tail. The project went on for 5 years and after an estimated $20 million spent, the easily distracted cat was killed by a taxi. The project was discontinued.

There’s so much we don’t know about the CIA’s operations, but then again, that’s the whole point of the CIA.

References

- “C.I.A. Reveals Some Old Tricks of the Spy Trade at Museum. The New York Times. The Associated Press. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- “CIA Developed Insectothopter in the ’70s.” UAS Vision. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- “Insectothopter: The Bug-Carrying Bug.” CIA.gov. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ” In the 1970s, the CIA Created a Robot Dragonfly Spy. Now We Know How It Works.” Popular Mechanics. David Hambling. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- The Black Vault.

- “CIA unveils Cold War spy-pigeon missions.” BBC. Gordon Corera. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- “When the CIA Learned Cats Make Bad Spies.” History.com. Retrieved June 13, 2020.